Past Zone -

News and Features celebrating the

past

617 Squadron Vulcans on deployment at Leeming in the 1970s - from Tony Eaton

Circa 1985 these photos from Tony Eaton show 74 Sqn Phantoms on exercise at Leeming

A 25 Sqn Tornado F3 as featured in the article below overflies Leeming - photo via Tony Eaton

" Just another Day at the Office"

Beechcraft B200 King Air G- PCOP at Staverton Airport. Video with permission of Cory Pockett

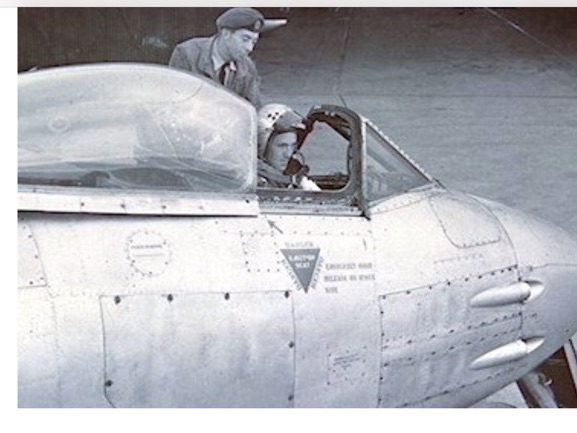

Flt Lts Mark Wilson &Ted Threapleton with their F3

This feature is from an original article written by Flt Lt Mark Wilson of XXV(F) Squadron

On Tuesday 28 March 2006, Flt Lts' Mark Wilson and Ted Threapleton of XXV(F) Sqn were planning a routine training mission in their Tornado F3 from Leeming.

It's a dismal day, with thick stratus cloud, westerlies up to 30 knts and showers everywhere. Not a great flying day, but as Ted and I are Falklands bound next week, these conditions are great training for the South Atlantic. Maps drawn, signatures done and our F3 is ready with 9 tonnes of fuel.

Ten minutes later, airborne over the Lake District and we receive a call from Scottish Military asking us if we can intercept and assist a small business aircraft in distress. We head north at over 700mph to our target flying south of Glasgow. After establishing radar contact, ScotMil informs us that the Beechcraft, flying in clear air at 15,000 ft and 220 knts, has lost all comms and navigation equipment. Despite his low speed we formate successfully alongside him.

Our plan is simple. Establish visual contact with him and using hand signals guide him into Prestwick. Mission accomplished, it's just another day at the office! Alongside I waggle my wings and he acknowledges my signal so we turn for Prestwick. He is reluctant to match our gentle turn and ends up astern of us where we can't have visual contact. We fly a racetrack pattern and pick him up again.We want him to follow us keeping slightly swept on our wing both maintaining visual. It is proving very difficult for him to maintain position. No problem as we are nearing Prestwick and can start a gentle descent to below cloud level, but the Beechcraft will not follow us! ScotMil tells us Prestwick is now no go due to the weather so we head for Edinburgh with Leuchars as diversion.

Regaining visual with the Beechcraft we head east pondering why the Beechcraft is reluctant to follow us through the cloud. Surely he can fly using his back up instruments? At this stage though a much bigger problem emerges. The Beechcraft has slowed to 150 knts, an airspeed that presents us with major problems. To give visual signals we must fly a few feet away on his wingtip, a challenge in itself. However with our fuel load and extra tanks this airspeed is 30 knts lower than our normal landing speed. They don't teach this on the OCU so it's all new ground now! Eventually we are over the North Sea and give visual signals for the descent into Edinburgh.

Again the Beechcraft refuses to follow our descent. Why will he not formate and follow us to safety? After this outburst Ted and I discuss whether his back up instruments are indeed working. “These are back up instruments and they always work !”

We formate with him again, requiring full flaps and reheat to keep position, then lower our gear to indicate landing and move ahead of him. Finally the message seems to work as the Beechcraft follows us in the descent but then the Beechcraft begins to diverge again. “If the Beechcraft will not formate on us I will formate on him!” I pull alongside only yards from his left wing to give him the feeling that we are heading in the right direction. The Beechcraft begins a gentle left turn.

We are in an area of cloud known to pilots as the “Goldfish Bowl” where you can only see other aircraft for a few miles. But the cloud is everywhere, above, below and all around. There is no horizon to indicate your attitude and it’s extremely disorientating. The Beechcraft tightens his left turn with us glued to his wing.

I then realise that the pilot has become totally disorientated with no awareness of which way his aircraft is pointing! I try to turn into him to force his wings level but his turn tightens towards me. His speed increases and his nose drops lower and lower. Turning tighter and speed increasing we are spiralling towards the ground with the G forces building rapidly. One more try to force him to level his wings but our situation is becoming perilous. I’m forced to break away as our altimeter unwinds rapidly with my heart racing!

“Ted, he’s lost it and he’s going in!” Ted is calling “Mayday, Mayday’ on all frequencies as we lose sight of the Beechcraft spiralling down into oblivion.

We fear the worst but then miraculously he reappears climbing rapidly in a slicing turn. He appears to have lost all control before disappearing again into cloud above us. We call ScotMil.

“Do you have radar contact with our target?”

“Negative” they reply.

The next few seconds seemed like a lifetime with different thoughts running through my head. "Why me?" "What happened?" "Have we just witnessed the last few seconds of their lives?" Post landing Ted and I discussed this particular moment and realised that we had been sharing the same thoughts and emotions. It was a horrible feeling and one that I hope never to experience again.

Suddenly, jolting me out of my thoughts, the radio crackles. "This is Scottish, we have radar contact, two miles south tracking west." The elation quickly disappears as we realise that the situation is even more perilous than we thought. Descent through cloud is not an option anymore as we have to assume that even his standby instruments have failed based on what we have just witnessesed. We find the Beechcraft again and decide that diverting into Leuchars is the best option, as anything could happen and at least we are over the sea and not any populated areas. Small gaps in the cloud eventually appear, so once again we try for a descent, picking our way through any gaps without entering cloud. Normally would simply invert, pull hard and zip through the gaps to descend quickly but can't do that with the Beechcraft in tow. After a 12,000 ft descent we break cloud and can lead the Beechcraft safely into Leuchars still flying uncomfortably slow. We land after the Beechcraft and look forward to a long chat to the pilot and his two passengers.

He informs us that he had a total electrics failure losing all comms and digital displays. Even worse his battery had also failed meaning his back up instruments were not available to him. The only reference available to him was a small cabin analogue readout which was effectively useless. This even for an experienced aviator is about as serious as it gets especially with the day's weather conditions.

Then for Ted and myself it was a quick refuel and back to Leeming to be greeted by the Station Commander and Press Officer. Congatulations all round and even a call from the Squadron boss in the United Arab Emirates. Our buddies quickly brought us back to earth calling us "heroes in our own lunchtime". All of this is followed by newspaper articles, radio interviews and even a live broadcast on Sky News, all praising our efforts. But is it all deserved?

Ted and I don't feel special just ordinary people who found ourselves in extraordinary circumstances. We were just in the right place to help and truly believe that anyone of us would do the same in the air or on the ground to save lives. Thankfully this incident had a happy ending but could easily have ended in tragedy. Life moves on and the Falklands awaits for Ted and I looking forward to counting the penguins!

Flt Lt Mark Wilson and Flt Lt Ted Threapleton were both awarded the

Queen's Commendation for Bravery in the Air

Weblink to the full AAIB Report for this incident here

- Beech_B200_King_Air_G-PCOP_06-07.pdf

- BeechB200 King Air G-PCOP Field Report

In writing this feature I am indebted to Group Captain (Rtd) Ted Threapleton for his help and Mark Wilson's original article.

Stuart Watkin, FLAG Chairman

Leeming Memories by Tony Eaton

Tony served at RAF Leeming from September 1956 until 1959 as an Airfield Crash Fireman. He returned in 1961 when the Air Ministry civilianised the RAF Fire Service and stayed until retirement in 1997.

Tony writes - during my service

at Leeming I collected numerous stories from personnel who were

serving at Leeming during that time. The first, is by my late

friend Flight Lieutenant Tom McCarthy DFC who served as an

Air Traffic Control Officer at RAF

Leeming.

Bomb Aimer Sgt Tom McCarthy arrived at Snaith near Goole, the home of 51 Halifax Squadron 4 Group in May 1943. After a period of `running in’ Tom was on Battle Order for July 12/13 and the target was Aachen in the Rhur. Approaching the target area they encountered heavy flak and the starboard engine was shot off its mounting. The aircraft remained airborne and they went into the bombing run dropped the bombs but it was then hit by an incendiary bomb dropped from an aircraft above which set fire to parts of the aircraft interior. Tom and the rear gunner both heavily dressed for the cold managed to put out the flames. They flew back on three engines and did pancake landing at Gatwick. A short while after landing, the Halifax burst into flames and was destroyed.

They were back on ops on the 24 July and the target was Hamburg, the first use of radar blocking Window. Midway way to the target the navigator reported to the Skipper that he was feeling ill and and that he could not continue and so they returned to base after two hours 57 minutes flying. A couple of nights later it was the turn of Essen, they bombed the target and were attacked by night fighters but returned safely. The following night it was Hamburg again but when they arrived at the dispersal, the navigator refused to enter the aeroplane telling all that they were for the chop. He ignored their pleas and so the wing commander was summoned and the navigator was driven away never again to be seen by the crew. The navigator was deemed to be LMF-Lacking Moral Fibre. He was stripped of his rank and given menial work for the duration of the war. Tom had noticed that he was very nervous with his continuous shaking of his hands long before the trip began.

The next night was Hamburg again with a fresh navigator, returning after a five hour trip. Tom and his green crew had truly been thrown into battle at a most brutal period which was known as the Battle of Ruhr. Losing their navigator meant they might have to fly with a spare navigator who had lost his crew. On August 17th they were on ops to attack the Rocket Research establishment at Peennemunde with a spare navigator. There were Halifaxes and Lancasters on the raid, the Halifaxes attacked in the first wave to bomb the laboratories and living quarters of the scientists and technicians with the express intent of killing them. The Halifax attack was fairly successful but the Lancasters in the second wave suffered appalling losses some forty aircraft being shot down due to the arrival of night fighters that earlier had been duped into thinking the target was Berlin. Tom dropped the bombs at a much lower altitude than any other target hitherto and they turned for home but were constantly attacked by a JU 88. The Skipper, skilfully using the corkscrew manoeuvre thwarted the German fighter pilot who after several unsuccessful attacks finally turned away.It was at this juncture that Tom and the other five members of his crew were returned to the Heavy Conversion Unit to train with a new navigator. The training lasted from August 1943 to February 1944. With being at the HCU they missed all the attacks on Berlin which were carried out over that winter period-save for one.

On the 15th February they were back on ops as a crew with their new navigator and the target was Berlin, the Big City. It was the largest force ever sent to Berlin in the entire campaign, 561 Lancasters and 314 Halifaxes. An uneventful approach to the target was being made and the Skipper asked the flight engineer for a fuel check. The F/E told the Skipper it was time for a change of fuel tanks. He proceeded to the rear of the aircraft plugged his oxygen mask into an auxiliary port intending then to open the fuel change over valves under the rest bed past the mid upper turret, but he collapsed almost immediately. His oxygen mask had become worn due to poor storage and he had passed out. In the mean time all four engines spluttered to a halt and the bomber began diving like a stone. The Skipper yelled to Tom to go and sort things out. Every member of the crew had some detailed knowledge of other crew member’s tasks. Tom knew the fuel change over technique and crawled up the diving Halifax and opened the fuel valves, the engines roared into life and the Skipper brought it on to an even keel. The F/E was soon sorted out and they proceeded to Berlin. Their aircraft had dropped from 20,000 feet to approx 10,000 feet and was now approaching the target. The Skipper, realising they would not be able to claim the lost altitude kept the Halifax at that 10,000ft.They joined the bomber stream and dropped their bombs not realising that there were hundreds of bombers approaching and above them doing exactly the same thing. Some 2,642 tons of bombs were dropped that night on Berlin. Thankfully not a single one hit that lone Halifax.

In the March Tom developed a severe ear infection and was hospitalised with delirium and was off sick for three weeks. On returning he noticed there seemed to be fewer aircraft on the station. He had missed the costliest bombing operation that Bomber Command ever undertook, Nuremberg, when 95 aircraft were shot down. Multiply that number by seven and you have the number of men who died. Tom’s Squadron No 51, had lost six aircraft with several others damaged out of a total 15 aircraft despatched.

Tom with his crew undertook another 27 ops attacking rail and oil locations, Villers Bocage and transport facilities to help with invasion that began on D Day. Some of the ops being carried out were in the daylight which didn’t please the crews one bit. On one daylight op they past formations of German bombers flying towards England. Also amongst his last ops were two trips to the dreaded Ruhr but by then the German night fighter force was a shadow of its former power.

In the July of 1944 Tom and his crew were screened from operations, they had come out of it unharmed after a very long and dangerous tour of operation, 31 bombing ops that had lasted a whole year. They were duly grateful. Tom had previously carried out five maritime operations in early 1943 with a squadron of Whitley bombers making a grand total of 37 ops.

Tom was commissioned and sent to train other bomb aimers and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. His citation was fulsome, stating that his dedication, skill and bravery was of the highest standard.He recalled in early 1945 when after a long and tiring night flying programme he was waiting for a bus to go to his rented rooms, when it arrived the conductor said ‘War workers only’ and prevented Tom from boarding the bus.

The European war ended and Tom much to his consternation was informed that he was on the list for the Tiger Force, aerial operations for the invasion of Japan. His wing commander spoke to him later and said `Tom you have done enough’ and took him off the Tiger Force list.

Tom stayed in the RAF after war and converted to navigator and flew firstly with Transport Command then Lincolns of 617 Squadron when on one night exercise he gave a Lincoln rear gunner the night off and took his place in the turret.

With the arrival of the mid 1950s Tom joined the first Canberra squadron which was a challenge being cooped up in that very cramped cockpit. He eventually joined a nuclear armed Canberra squadron in the 2nd TAF in Germany in the early part of the 1950s. He did tell me personally that if it all was to happen his target was in Poland.

Tom’s flying career came to an end with the 1957 defence cuts which predicted that manned aircraft would be phased out in favour of the missiles. Still waiting?

He Trained to be an Air Traffic Controller and served at RAF Leeming, RAF Topcliffe and RAF Dishforth and a short spell as a fighter controller where he once described watching his ‘target’ aircraft that seemed to ‘stand still’ on the scope, it was a Lightning doing a vertical climb.

Tom left the RAF in 1977 and was the last wartime aircrew Officer to be honoured with a farewell Dining in Night at the Officers Mess at RAF Leeming. He worked as an air traffic controller for the helicopter units operating in the North Sea oil industry until retiring ten years later.

Squadron Leader Peter Odling - A Leeming officer's memories - by Philip Sedgewick

His first taste of military aviation was not a happy experience. Growing up near the famous wartime fighter base RAF Hornchurch, he was machine gunned by low-flying German aircraft on his way to school.

Joining the Air

Training Corps at 14, his headmaster permitted him to miss

Wednesday afternoon games and spend the time at RAF Hornchurch

cadging lifts from benevolent Reservist pilots. By the time he left

school Peter had over 200 hours as a passenger and a good idea how

pilot an aircraft.

Awarded a flying scholarship by the Air Ministry at 17, he joined

the RAF in 1952 and was classified as A1: G1: Z1- fit to be a

pilot. He proved the point by going solo after just three hours

tuition.

Receiving his “wings” he was posted to the Advanced Flying School

at RAF Middleton St George, now Teesside Airport. The aircraft he

now progressed to was the Gloster Meteor, the RAF‘s first jet

engined fighter. When he took his first flight in this powerful jet

he had yet to reach his 19th birthday.

Ironically, although he could shoot up to 35,000 feet and fly at

600mph, he couldn’t vote and didn’t even have a driving

licence. Camaraderie amongst the young pilots was

something he well remembers. He said: “It was a different air force

then; we lived in huts and ate in the mess.”

Peter did eventually

buy an Austin 7 from a local scrapyard for £7; although he is

rather coy about how they spent the rest of their spare time.

Selected for bombers he flew the Lincoln a descendent of the

wartime Lancaster shuttling the four-engine aeroplane across,

Europe and the Middle East, still at a relatively young age. He

recalls it was very cold, very noisy and little different to its

wartime predecessor.

Posted to a Canberra Squadron in West Germany and then back to the

UK, he became an instructor at Cambridge University Air Squadron.

One of his pupils who he persuaded to join the Air Force

subsequently rose to be operational head of the RAF: Air Chief

Marshal Sir Michael Stear. “I was very proud of that”, he

recalls.

Out of the blue he was posted to the V Bomber Force as a Captain of

the RAF’s cutting-edge aircraft: the mighty Vulcan.

With the Cold War in deep freeze, after ground school and flight

simulation he was soon up to scratch. One of his early trips was

halfway across the Atlantic; returning they were forced to divert

to Prestwick where the aircraft was put under armed guard whilst

the aircrew were put up for the night in a local hotel -a rare

treat.

Their home squadron was 617 (Dambusters) and they were very proud of that. They had the same offices and hangers as the wartime Lancaster crews.

Armed with the Blue Steel, a forerunner of a modern-day Cruise Missile their given task was to destroy a designated target in the Soviet Union in retaliation for a nuclear strike on the west.

The shooting-down of the American U2 spy plane in May 1960 was a game-changer, forcing a switch from high-level to low-level strikes. The Vulcans went from white paint to camouflage. Now they flew below treetop height and their missile launch reduced from 200 miles to 20 from target.

Crews were regularly on a state of readiness: Quick Reaction Alert, waiting to respond to the nuclear threat. QRA still operates at both RAF Coningsby and Lossiemouth today.

Often their skyward

practice sorties involved the whole V Force of over 80 aircraft,

terrifying the civilian air traffic controllers and playing havoc

with television broadcasts over Scotland.

In truth aircrews had an idea that the simulated attacks were

exercises as there hadn’t been the increased political

tension. Although Peter did recall an occasion he was on

QRA cockpit readiness and it was quite some time before they were

stood down and believed it was the real thing.

For the five-man crew of: pilot, co-pilot, air electronics officer, navigator plotter and navigator radar flying the Vulcan did have its dangers. Only the pilot and co-pilot had ejection seats, the remaining ‘back seat’ crewmembers had to bail out through the entrance door: a process not always successful when an aircraft had to be abandoned.

Luckily during his

long career Peter only had one mishap when an engine failed on

take-off but he successfully returned to base.

A further move to RAF Finningley as a Chief Flying Instructor then

a ‘hush hush’ job in Malta and finally to RAF Leeming as Chief

Ground Instructor. He left the RAF after 22 years with the rank of

Squadron Leader.

After working for Portakabin, he ran his own TV/Electrical business in Thirsk. On retiring he resumed flying at Bagby Airfield using a friend’s aircraft. He became a sought-after speaker and Chairman of the Flying Club and is also highly-skilled at repairing model locomotive engines.

“I gave up flying completely at the age of 75. I thought that was just the age to start becoming dangerous, after all it is not like a car that you can park at the side of the road if anything goes wrong.”

During his distinguished career Peter amassed over 4500 flying hours, the equivalent to spending six months constantly in the air. He has flown 14 different types of aircraft, 56 out of the 82 Vulcans built including those on display at the Sunderland and Newark air museums and even broke the sound barrier in a Hawker Hunter.

Looking back,

Squadron Leader Odling believes they were justified being resolute

in their daunting task.

“We didn’t agonise even

though we knew that if we had to go for real, we wouldn’t be coming

back as there would be nothing

there.

“That was our mind-set over the years and we took it all in our stride.

“You were in the Royal Air Force and it was the Cold War.”

Middleton St George Memorial Association

Annual Remembrance

2019 Ceremony

2018 Ceremony

With the impending closure of the St George Hotel at Durham Tees Valley Airport the Middleton St George Memorial Association held what could be it's last Remembrance Service there on Saturday 10 November 2018 and there was an excellent turn out of both veteran's and serving RAF personnel .

The Address was given by the Reverend Colin Lingard and wreaths were laid by representatives of the Air Cadets , the Royal Air Forces Association and Shaun Woods on behalf of Durham Tees Valley Airport.

Wreaths were also laid by the Royal Canadian Air Force representative Captain Stuart MacWilliams, a CP-140 Aurora pilot currently on an exchange posting with 56 Squadron at RAF Waddington and Squadron Leader Phil Stewart of 100 Squadron at RAF Leeming .

Personal tributes were made remembering those that had 'Failed To Return' .

David Thompson

Rededication of the Cheviot Memorial

A new memorial to allied airmen who lost their lives in the Cheviot Hills of Northumberland in the Second World War, and the shepherds who tried desperately to save them, was unveiled by His Royal Highness, the Duke of Gloucester in one of the final events to mark 100 years of the Royal Air Force.

The memorial, set against the stunning backdrop of the Northumberland National Park, was overhauled as an RAF100 legacy project, with fundraising led by the Alnwick and Rothbury branches of the RAF Association. Originally unveiled in 1995, the polished granite and bronze memorial has been updated to recognise the courage of the shepherds who rescued and cared for some sixteen airmen who survived air crashes.

A moving ceremony was attended by the Duchess of Northumberland, Civic Dignitaries, Senior Royal Air Force Officers, veterans, local farmers and shepherds. A guard of honour was provided by personnel from RAF Boulmer , whilst a Hawk jet from RAF Leeming’s 100 Sqn flew through College Valley for a poignant a low-level flypast.

Wreaths were laid by Air Force representatives from New Zealand, Canada, Australia, America and Germany. Lieutenant Colonel Stefan Kershner from the German Air Force said: “I really appreciate the friendship that has been shown to me today and that our loss has been included.”

There were several stands for those attending to visit, including Royal Air Force Association and the Mountain Rescue Team based at RAF Leeming, members of which took part in the ten-mile Cheviot Bomber trail race raising funds for the memorial earlier this year.

The Duke concluded the event by unveiling a commemorative plaque in Cuddystone Hall, He said: “I congratulate you all for restoring and rededicating the Cheviot Memorial and for including a memorial to those who were not part of combat.”

September 2018

Photo - P. Charlton

Andrew Mynarski Statue and RCAF Memorial Garden

The present Durham Tees Valley Airport was previously RAF Middleton St George which operated as a bomber airfield during the Second World War. In June 1944, Lancaster KB726 of 419 (Moose) Sqn, RCAF, part of 6 Group Bomber Command, was taking part in an attack on the rail junction at Cambrai. It was fatally attacked by a Ju88 which left the aircraft burning and rear turret jammed, trapping the gunner, F/O George Brophy. Delaying his orders to abandon the aircraft, the mid upper gunner, P/O Andrew Mynarski attempted to free his fellow gunner, Brophy despite his own clothes being on fire. After unsuccessfully attempting to move the turret, Mynarski was told to jump by Brophy before it was too late. In a final gesture to his friend, Mynarski stood to attention and saluted the trapped George Brophy. By now his clothes and parachute were burning fiercely and sadly Andrew Mynarski died from his injuries shortly after being found by French civilians. All the Lancaster crew survived, including George Brophy, remaining in the rear turret which had stayed intact in the crash.

On the crew’s return to England after the war they told of Mynarski’s amazing courage for which he was awarded the VC on 11th October 1946. In recognition of his courage, a statue of Pilot Officer Andrew Mynarski was erected in the RCAF Memorial Garden at the St George Hotel following a successful campaign locally. The photographs were taken at the Rememberance Ceremony in June 2008, attended by veterans, local groups and officials, the Canadian and Royal Air Force, friends and members of the public. Following the ceremony and marchpast by veterans, a Hawk from our host 100 Squadron at Leeming, made a salute flypast in clear bright sunshine.

For more information follow the links below.

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/phillip.charlton/mynarski.html

http://www.northeasthistory.co.uk/the_north_east/history/wwtwo/forgottenhero/index.html